Explainer

The Best & Worst Countries for Animal Welfare Are Difficult to Measure

Law & Policy•7 min read

Reported

Workers were told their injuries were “break-in pain,” soreness that comes from adjusting to life in a meatpacking plant. But some injuries were much more severe.

Words by Madison McVan, Investigate Midwest

In the cold packing department of Seaboard Foods, Melissa Bailey was boxing up a cut of pork when she lost her balance. The box she was holding slipped from her hands. She fell to the ground. When she got up, her left hand stung.

A nurse told her it was “break-in pain,” but Bailey insisted that this pain was different from what she experienced in her first months on the job, she said. The nurse massaged her hand and sent her back to work, though Bailey kept returning and asking for help, only to be turned away. She eventually notified the union, which helped her secure an X-ray at a local clinic.

The doctor determined Bailey’s hand was sprained and sent her back to work with a doctor’s note requesting a less taxing position.

Instead, management reassigned her to a more difficult task, lifting even heavier portions of meat than before, she said.

In an industry known for severe injuries, Seaboard Foods, the country’s second-largest pork producer, appears, on paper, to be a safer workplace than many of its competitors. Data it has to report to the federal government claim workers suffered fewer injuries compared to the plant’s peers.

In the past five years, the Guymon plant’s incident rate—the number of injuries and illnesses at the plant divided by the number of hours all employees worked—has remained around 1, according to an Investigate Midwest analysis of data the company provided to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. That’s well below the industry’s median incident rate for that time period of about 4.

Meatpacking plants are supposed to report to OSHA all injuries that require treatment beyond first aid, and workplaces with higher injury rates face more scrutiny from the federal agency.

But seven former and one current Seaboard employee told Investigate Midwest their serious injuries—ones that required treatment beyond OSHA’s definition of first aid and often needing X-rays or MRIs—were treated like minor scrapes or bruises.

The Investigate Midwest investigation found:

Seaboard’s “disregard for the wellbeing of their workers is completely adverse and grossly disconnected with the realities of these employees in this plant,” said Martin Rosas, the president of UFCW Local 2, the union that represents Seaboard’s workers.

Seaboard Foods did not make plant management or company executives available for interviews despite several requests by Investigate Midwest. Instead, a spokesperson responded by email and denied some of the allegations by former employees.

“Our employees’ safety is always our top priority, and this is the guiding principle for any decisions we make as a company or program we put in place,” Seaboard Foods spokesman David Eaheart said in the email. “To that end, we continually modify our processes and equipment, create additional positions where needed and provide ongoing training to help ensure each worker’s job assignment is manageable and safe.”

Eaheart said that Seaboard employees have a right to decline work reassignments. But Rosas said workers like Bailey are rarely given a choice in their assignment to a new position, and workers interviewed by Investigate Midwest said they felt they didn’t have a choice.

Read Seaboard’s full statement here.

The plant is owned by Seaboard Corporation, a publicly traded Fortune 500 company with international investments in food, energy and transportation. It owns Butterball, a staple of Thanksgiving dinner, and has a close business partnership with Triumph Foods, another large meatpacking plant. Seaboard sells pork under the brands Prairie Fresh and Daily’s Premium Meats.

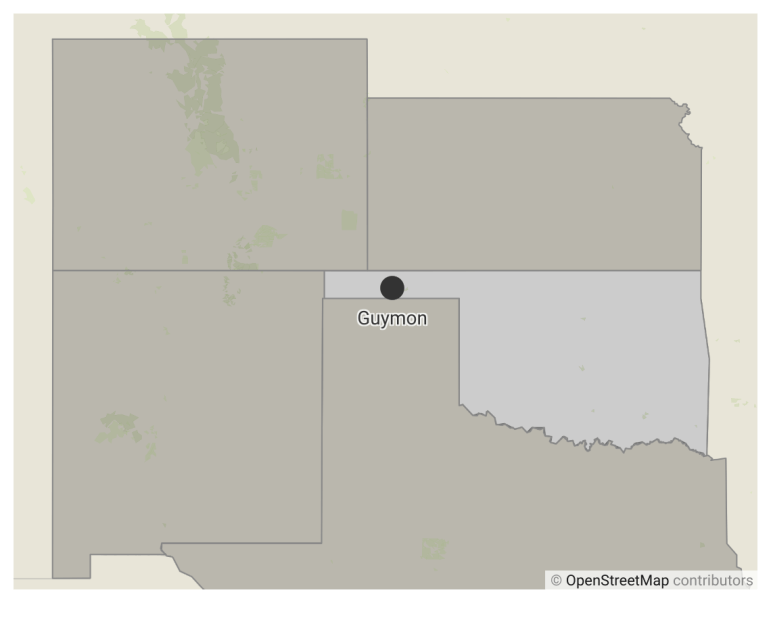

Situated in the remote panhandle region of Oklahoma, Guymon is home to around 11,000 people. When Seaboard Foods opened in 1995, it transformed the small ranching town into a hub for pork processing and brought in thousands of immigrant workers to staff the plant. Today, the plant employs more than 2,500 people.

More than one-third of Guymon residents are foreign-born and nearly 60 percent of the population is Hispanic.

On a recent August day, a perpetual stream of dusty aluminum livestock trailers passed by the truck stops, churches and Mexican restaurants that line the town’s main streets. A billboard two miles down the road from Seaboard Foods advertised job openings at a JBS plant in Iowa in English and Spanish.

Like many towns dominated by meatpacking, the pandemic hit Guymon hard. More than 40 percent of the plant’s workforce tested positive for the virus, and several died.

But, in another sign to the union that the plant downplays workplace injuries and illnesses, Seaboard Foods only reported a few “respiratory conditions” to federal authorities in 2020, sparking a complaint by the workers’ union.

Kristen Kinsella, 20, started working at the Seaboard Foods plant right after high school. She started out trimming meat in May 2019 but was quickly promoted to supervisor, where she was responsible for making sure her section of the line hit production quotas, and then to manager.

As she moved up the ranks, she grew frustrated with the treatment of workers—including herself—and became a steward for UFCW Local 2.

As a union steward, she accompanied employees to their meetings with the human resources department to bear witness, inform the workers of their rights and monitor the company’s actions.

In those meetings, she saw some human resources employees blame injuries on “break-in pain” or deny that their injuries occurred at work, she said.

Because meatpacking jobs are so physically demanding, most new employees go through a period of muscle soreness from adjusting to the backbreaking work. But even after the initial soreness faded, some members of the nursing staff would misdiagnose injuries as break-in pain, Kinsella said. She added that some nurses didn’t accommodate outside doctors’ notes or grant time off.

The situation forced injured workers to choose between pushing through the pain and calling out of work, which results in a “point” added to the employee’s record. Once a union member reaches 12 points, they can be fired.

Eaheart said in a statement that the “points system is not a disciplinary tool and does not adversely impact an employee for being late from a break or reporting an injury more than 24 hours after it occurred.” He said employees who’ve received medical care for a work-related injury or illness “will not receive attendance points for absences related to that injury or illness.”

In order to receive medical leave and avoid accumulating points, an employee must receive a form from the nursing staff, have their doctor fill it out, then return it to the plant’s medical staff. If an employee is assigned restrictions on what work they can perform, the employee has a right to accept or decline the alternative work assignment, Eaheart said.

“Seaboard Foods never terminates an employee because they are on Restricted Duty and will always find an opportunity for the employee to work in a new role that is in line with their restrictions if they so choose,” he said.

Seaboard Foods also has a “Work Hardening” program that conditions new employees by incrementally increasing their workload over four to six weeks until they reach full capacity. Three former employees and one current employee interviewed by Investigate Midwest said they were asked to perform a full workload before finishing the Work Hardening program.

“It’s all about getting product out and how fast we get that product done,” said David Klein, 30, who worked at the plant until December 2019.

When Klein felt something “pop out” in his back as he moved 40-pound sections of pork ribs from one belt to another, he notified his supervisor, who told him to go to the nurses’ station during his break. Klein worked through the pain until his break time, then went to the nurses’ station, where he was given ice and painkillers.

But the break was only 15 minutes long, and it took several minutes for Klein to get from his position to the nurse. He was late coming back and his supervisor berated him when he rejoined the line, Klein said.

Klein saw a doctor after work and was diagnosed with an inflamed disc and a strained muscle. The doctor’s note prescribed a week of rest, but the company didn’t grant him the time off, Klein said. Instead, he had to call out each day for a week, getting a point each time.

By the time he returned to work, he was only two points away from being fired.

(The company did not directly respond to Klein’s experience.)

In 2019, the U.S. Department of Agriculture implemented a rule that would eliminate limits on the speed of pork production lines as long as the facilities met food safety standards.

At the time, Francisco Reyes was working in quality assurance. Squeezed into the small space between a table and a conveyor belt, Reyes visually inspected each pork loin that passed him. When he spotted a defect, he twisted his body 180 degrees to toss the chunks of meat—some weighing more than 20 pounds—onto the table behind him.

After 10 years of working in meatpacking plants and 11 months at Seaboard, he had long gotten past the break-in pain that employees face in their first few weeks of the job. But as the speed of the production line increased he struggled to keep up with the pace and developed chronic pain in his back, so he asked to transfer to a position with a lighter workload, he said.

Instead, he was sent to the picnic line, notorious within the plant for its toll on workers’ bodies, Reyes said. There, he constantly tossed pork shoulders from one conveyor belt to another, raised belt.

“We have to toss those pieces up into the incline nonstop,” Reyes said. “Nonstop. The arms, they start to give out. And that’s when I heard a pop in my elbow.”

He visited a nurse and was given ice and painkillers, and then returned to the picnic line.

Later, MRI scans and an X-ray showed he had a fracture in his vertebrae and a contusion on his elbow, Reyes said. He brought a doctor’s note to work asking for restrictions on what movements he could perform while he sought treatment.

Reyes said a human resources representative told him the company wouldn’t accommodate his restrictions, and he was still one month away from qualifying for federally-mandated Family and Medical Leave, which provides up to 12 weeks of job-protected time away. He faced a difficult choice: Stay home without pay, or work through the pain. He needed the money, so he called the doctor and asked the restrictions to be removed, he said.

The next day, he was back on the picnic line, throwing chunks of meat onto the inclined belt. He was fired in June 2020 after missing too many days of work due to the pain.

Reyes filed for workers’ compensation and the case was still pending as of publication. He needs spinal surgery, he said, but can’t afford it.

“I will get the treatment that I deserve,” Reyes said. “That’s all I’m looking for now.”

Four other current and former employees who got hurt at Seaboard told Investigate Midwest that the pace of work contributed to their injuries.

United Food and Commercial Workers and three local chapters—including Local 2, which represents Seaboard employees in Guymon—sued the USDA in 2019 in an attempt to reinstate previous limits on how fast production lines could go.

A federal judge sided with the workers’ union and reinstated speed limits in March, giving pork plants 90 days to comply with the change.

The judge’s ruling cited a 2016 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office that found “line speed—in conjunction with hand activity, forceful exertions, awkward postures, cold temperatures, and other factors such as rotation participation and pattern—affects the risk of both musculoskeletal disorders and injuries among workers.”

Seaboard Foods, having already invested $82 million in increasing the pace of slaughter in Guymon, asked the judge in April to give the company 10.5 months to comply with the reinstated limits. The judge denied that motion in May.

Eaheart did not directly address line speeds in the company’s response to questions.

Kinsella, the former manager and union steward, said, in her opinion, plant management would make every effort to avoid paying out workers’ compensation or calling the attention of OSHA.

Seaboard Foods’ policies require employees to immediately report any injury to their supervisor. Then, the supervisor must escort the employee to the worker’s station for triage and evaluation, Eaheart said.

OSHA requires companies to document and report all injuries and illness resulting in medical treatment beyond first aid, days away from work, restricted work or transfer to another job.

OSHA does not require all injuries be recorded. If only “first aid treatment” is administered by nurses, such as bandages, ice or non-prescription painkillers, the company does not have to report the injury to federal authorities.

Kinsella said if an employee waited more than 24 hours after the time of the injury to report it to their supervisor, plant management would no longer consider it “work-related” because the employee has no proof that the injury occurred at work rather than in their off time.

Eaheart said, “there is no time frame for when employees are required to report injuries in order to receive care.”

Some people don’t know they’re hurt until days after the pain begins, Kinsella said, because workers may assume the pain is routine before realizing something is wrong when it doesn’t go away.

She also said that even if an employee did report an injury to their supervisor in the 24-hour window, supervisors didn’t always document the report. Kinsella said she saw some employees punished because their supervisors didn’t complete their side of the injury report and later blamed the lack of documentation on the worker.

Supervisors were incentivized not to report injuries because, if an employee transferred out of their area due to pain or injury, the supervisor’s employee retention rate would drop, Kinsella said.

“It wasn’t in their interest to do so,” she said. “If your retention rate sucks, they’re not going to give you a new hire, so you’re stuck with less people. So you’ve got to try and keep what you have.”

She said this also applied to behavior issues.

“In some areas, they’ll keep whoever, no matter how they’re treating each other,” Kinsella said.

Aggressive drug testing at the nurse’s office also dissuaded workers from reporting injuries.

One current employee in his 20s who wishes to remain anonymous to protect his job said he has avoided the nurses’ office for this reason. He can’t close his hands because they’re constantly inflamed from using metal hooks and knives. The pain keeps him up at night, and marijuana helps him sleep. He takes 10 ibuprofen before going into work so he can avoid the nurse, he said.

Eaheart, the company’s spokesman, said drug tests are used in cases of serious injuries.

“In some cases when a significant injury or illness is reported, Seaboard Foods may conduct a drug test to help determine the cause of the injury or illness, especially for safety-sensitive jobs,” he said. “If an employee is reporting to the first aid station for minor first aid needs—getting a Band-Aid or ibuprofen—they will not be subjected to a drug test.”

When the coronavirus pandemic struck the plant in Guymon, more than 1,000 employees got sick and six died, according to the company. But, according to OSHA documents, Seaboard only reported 3 respiratory illnesses to OSHA in 2020.

The workers’ union filed an OSHA complaint in April against the company for failing to report all illnesses and for not enforcing coronavirus mitigation measures like social distancing.

Now, Rosas, the local union president, suspects the same underreporting is happening with injuries.

Eaheart said Seaboard Foods reported about 20 injuries to OSHA in 2019 and about 30 in 2020.

Workers’ compensation claims alone account for 18 injuries in 2019 and 13 injuries in 2020.

“I do believe, in my personal opinion, that Seaboard is doing not much different than what they did with COVID,” Rosas said. “They’re underreporting that people are going to the nurse’s station.”

Visits to the nursing station do not have to be reported unless the injury requires care beyond first aid.

“All injuries or illnesses that meet the definition of an OSHA recordable have been logged,” Eaheart said.

Bailey, the packing worker who sprained her hand, said she left Seaboard Foods for good in December after receiving a write-up for dipping her hands in a bucket of warm water—something she and the other workers on the line regularly did to warm their hands in the cold room and relieve their pain.

But the plant left her with more than just physical pain. From Jamaica, she said she encountered racism and personal attacks from coworkers and supervisors.

On one occasion, a cafeteria worker accused her of stealing because she brought yogurt from home and human resources threatened to ban her from the cafeteria. When she threw away a cracked face shield and requested a new one at the PPE station, the woman refused to issue her a new mask and instead told Bailey to dig the old one out of the trash.

When she slipped and fell a second time, a supervisor called her a “troublemaker” and another manager insinuated that Bailey was illiterate, Bailey said.

Eaheart said the plant has a “zero-tolerance policy for discrimination or harassment in the workplace and all employees have the right to be treated with fairness, respect and dignity.” Employees can report incidents of discrimination to supervisors so the company can take “corrective action,” he said.

Bailey can’t talk about her time at the plant without crying.

“It doesn’t make no sense how they treat people,” she said. “It just makes me sad.”

Investigate Midwest is a nonprofit, online newsroom offering investigative and enterprise coverage of agribusiness, Big Ag and related issues through data analysis, visualizations, in-depth reports and interactive web tools. Visit us online at www.investigatemidwest.org