Explainer

Organic Farming: What It Is — and Isn’t — Explained

Food•7 min read

Reported

Over the last few weeks, severe winter storms have pelted the U.S. agriculture industry with problems, killing hundreds of thousands of animals.

Words by Holly Pate

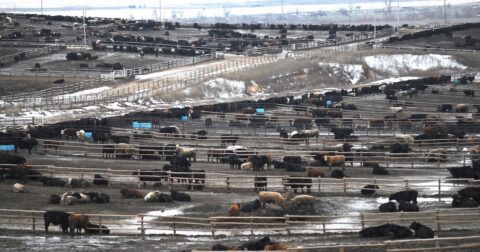

Over the last few weeks, severe winter storms have pelted the U.S. agriculture industry with problems. From Nebraska to Alabama, farmers battled with snow, hail, and freezing temperatures that threatened processing, disturbed deliveries, and killed hundreds of thousands of animals.

In Arkansas, ranchers pulled pantyhose over the heads of calves to act as winter beanies, while in Missouri a family farm reported using anything from blow dryers to space heaters to keep barns warm. In Montana, some farmers reported duct-taping calves’ ears to their necks to keep them from falling off. And in Louisiana several poultry facilities collapsed from the build-up of snow and ice, killing thousands of birds.

With calving season underway, farmers such as Jay Volk and his brother Clark in Nebraska cannot afford to miss one birth, especially when one of their young bulls can ultimately sell for $4,000. They slept in shifts on recliners inside of barns to keep constant watch of more than 170 cattle births. However, researchers estimate that thousands of newborn calves died shortly after their birth in many Midwest and Southern states.

“They are pretty wet when they’re born,” Jay told the Omaha World-Herald. “Two hours outdoors in this weather and they are done. They are dead.”

The nation’s total economic impact from its recent storms will be between $45 and $50 billion, AccuWeather estimates. Though experts say it is too soon to predict the total amount of revenue lost specifically in the agriculture industry, these disruptions and the loss of livestock life are anticipated to cost ag companies and farmers millions.

Initial Texas agricultural loss estimates alone exceed $600 million, with citrus, livestock, and horticultural crops specified as the sectors that were hit hardest, according to preliminary data from Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service economists. Almost half of the total revenue loss relates to livestock including cattle, sheep, and goats, and their offspring that died or were badly injured.

“A large number of Texas farmers, ranchers, and others involved in commercial agriculture and agricultural production were seriously affected by Winter Storm Uri,” Jeff Hyde, Ph.D., AgriLife Extension Director at Bryan-College Station, said.

Hyde cautioned that freezing temperatures and ice, harming crops and livestock, could cause residual costs that will plague producers for years to come. Immediate livestock loss estimates include initial costs related to animal deaths, damage to housing facilities, and inflated heating bills. But cost caused by decreased beef cattle weights, dwindling milk production, and lingering fertility issues could bring much more severe long-term consequences for generations of animals (and producers) to come.

Researcher, Sandy Johnson, an Extension Beef Specialist in Colby, Kansas, agreed that the impact of the cold weather experienced in Kansas and surrounding states in early February will not be forgotten anytime soon and might leave lasting effects, specifically in the cattle industry.

“I have heard of calves with frostbite damage to ears, noses, tails, and feet. Damage to feet may require euthanasia as there is nothing to be done after the fact if the case is severe,” Johnson said. “I expect there will be lots of calves that will be sorted off to be sold at a lower price at auction time because of short ears and tails.”

Johnson also worried about a lack of adequate bedding and wind protection needed to prevent scrotal frostbite in bulls, which may dramatically affect their fertility and future offspring.

Johnson explained that discovering later that your bull was suffered from weather-related fertility issues during the breeding season is another pricey problem, resulting in a significant decline in pregnant cows, and ultimately calves.

Although much of the ice has disappeared and pastures are drying, producers must continue to be vigilant as the weather warms, according to Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service experts.

Farmers are warned to look for latent effects of frostbite damage on tails, ears, teats, udders, and scrotums. Raw or bleeding skin or scabbed over areas could indicate previous frostbite and affect reproductive function or cause infection, experts said. Cows with frostbitten udders or teats may be extra sensitive, reducing milk production and consumption by their calves for a few days to weeks.

Disease caused by physical stress will also be heightened for the remainder of the breeding season, experts warn. Stressed farm animals are more susceptible to internal parasitic infestations, such as stomach worms, and those kept near wet hay or bedding are at higher risk of contracting coccidiosis, a disease that affects their intestinal tract.

The freezing temperatures have also killed much of the pasture herds graze on, and as warmer weather shifts snowy landscapes to muddy fields, more bedding will need to be put down, Anne Kimney, a ranch owner in Oklahoma, said. As the temperature fluctuates older cattle are also at higher risk of respiratory illness, she added.

Experts say as climate change continues, severe weather events like these could become the norm, and farmers and ranchers should continue to think of ways to protect their animals, but also consider winterizing equipment for colder seasons to come.

“We can always be better,” Kimney said. “We don’t know the challenges that we’re going to face but I think you just do the best you can always.”