Solutions

Fishing the Ocean’s Twilight Zone Comes at a High Cost

Climate•7 min read

Perspective

Animal liberation won’t happen until Black, Brown, and Indigenous people have equity in the animal protection movement.

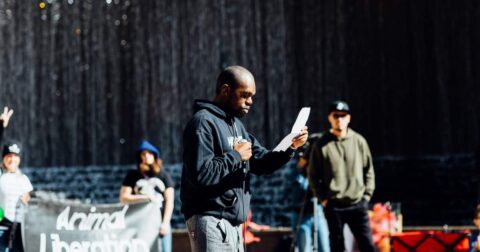

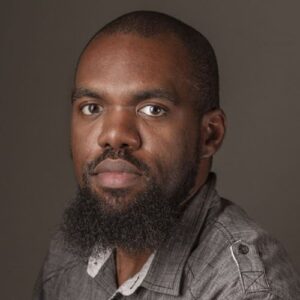

Words by Christopher "Soul" Eubanks

As a child, I read about civil rights activists’ many experiences and the onslaught of resistance they faced in their pursuit for equality and a just world. Many of them were subjected to being water-hosed, having animals weaponized to attack them, and racist mobs physically and verbally abusing them as they advocated.

You know the story. Racist white folks in the 1960s embraced confederate flags yelling slurs and chanting “white power, ni**er, fu**ing ni**er.” But this abuse is not a thing of the past.

These same slurs were yelled at me at a rodeo protest in 2020. While the racism I have experienced throughout my life has typically been more covert and systemic, this was the first time I experienced hostile, overt, aggressive racism directed at me.

After doing animal rights activism for over three years and attending over 100 events, I am used to being the only Black person in the room. But this rodeo was the first time I was the only Black person surrounded by a growing mob of white people who were becoming increasingly agitated and aggressive as our protest continued.

At that moment, I couldn’t help but think about the civil rights activists that I learned about in school who paved the way for me to be standing where I was at that very moment. I felt a connection with them through this experience—and I know I’m not alone. After the protest, I began to reflect on how my experiences as a Black man in the United States shaped my passion for advocacy work and prepared me for moments like this.

During my teenage years, I became very aware of how race impacts not only society but also my very own psyche. The more I began to self-educate and learn about systemic oppression—such as the school-to-prison pipeline, the transatlantic slave trade, the suppression of Black peoples’ contributions to modern society, and more—the more I began to understand the totality of white supremacy. My worldview became darker, and while I didn’t have hatred towards white people as individuals, I did start to view white people collectively as a group as oppressors.

Being raised in a low-income Black community and seeing predominately white people hoard social, economic, and political power positions strengthened my view of the US as the ultimate symbol of white supremacy. As I learned about the FBI’s Cointelpro operations, the experiments done on Tuskegee airmen without their consent, the hyper-criminalization of Black people with Rockefeller drug laws, and more, I began to grasp how racism had now become more entrenched than ever.

I also became much more aware of how often I was the only Black person surrounded by mostly whites, and I became anxious every time I was in this predicament.

I often told myself I was just being aware of my surroundings, but eventually, I had begun to distrust white people. It took years for me to understand and shed these feelings of bitterness, and I can honestly say that without this extensive internal work to overcome my anxiety, there is no way I would have been able to be a part of the animal rights movement today.

Being vegan can be a lonely endeavor. But being Black and vegan, specifically in the animal rights community, has brought me additional isolation that I was unprepared for. Even though being the only Black person in a predominantly white setting isn’t new to me, it’s perplexing to feel this within a social justice movement.

Initially, this feeling of isolation was uncomfortable, but over time, it’s become normalized—and I have found myself noticing it less. I have wondered why there aren’t more Black people in the animal protection movement. On the surface, I understood that many marginalized people don’t feel they have the luxury of advocating for others when their own freedom is—and has historically been—attacked. But what I hadn’t before considered was whether the animal rights movement put much effort in making Black, Indigenous, and people of the global majority feel included.

On several occasions, I have been asked by white folks how the animal protection movement can include more Black people. I understand there are good intentions behind this. But questions like this often give me mixed feelings because while I believe I have valuable insight, I don’t want my perspective to be seen as the definitive voice of all Black people. Black people are not monolithic.

One time, a close friend saw me participating in an animal rights march and was curious to know if any other Black people were attending because she didn’t see any. There were only a handful of Black people in this march of close to 100 people, but that moment reminded me why it’s essential for the animal protection movement to understand how we are perceived.

To Black people and non-vegans of all races, the animal rights movement can appear as an affluent far-left group who ignore the systemic oppression they have benefited from while using that affluence to advocate for non-humans. Far too often, white animal advocates are offended when inequity within the movement is addressed, but this is constructive criticism which they should heed to grow this movement.

Had I been vegan when I was 15 or even 25, there’s no way that I would have gotten involved in this movement. Beyond my introverted ways, the anxiety of being surrounded by whites would have deterred me from being involved in animal protection. I am now strengthened by the understanding that while racism has victimized generations of Black people, it has also cheated our entire society.

We’ve all been raised in a culture that sanctions using our differences as tools of oppression. This realization made me sympathetic towards individuals who perpetuate oppressive thinking, and I now hope that one day they’re able to grow beyond their toxic cultural conditioning.

While I am no longer triggered when I am the only Black person in the room, I’m certain countless Black people currently feel the way I felt and are apprehensive about participating in activism dominated by white people.

When I first began doing animal activism, I was inspired by an incredible Black woman working at a major animal rights organization. I met her at one of the first protests I ever attended. It was comforting seeing another Black activist amongst a predominantly white group.

We talked throughout the protest, and she told me about the struggles she faced helping her co-workers understand why a plant-based diet wasn’t as easily accessible to Black people in marginalized communities as they may be for whites. She shared various tales about how insensitive many of her co-workers were to the fragility that exists in predominantly white animal protection organizations.

Although veganism can be achieved on a variety of budgets and in a variety of ways, the lack of understanding towards systemic issues that persist in communities of color is a prime example of why this movement has to be more diverse to achieve animal liberation. We need representation at all levels.

Non-human animals are systematically killed by the trillions every year, making them statistically the largest group of oppressed beings on the planet. But as humans who are advocating for them, we have to be aware of how human-based social issues impact the animal protection movement. Ignoring social justice allows inequity to thrive, leading to turmoil and internal conflict within the movement. Ultimately, ignoring social justice deters the progress we can make for the animals.

Some white advocates feel that by addressing human rights issues in the animal rights movement, we’re being counterproductive to our cause and doing a disservice to the animals. This normalization of ignoring other forms of oppression has been used to build the framework for much of the culture in the animal rights community today.

While I don’t believe this exclusionary approach to activism is exclusive to the animal rights movement, we see it starkly, especially in this moment of racial reckoning our society is facing. I understand the importance of making sure animals don’t become overshadowed in the movement dedicated to them, but we must recognize that other forms of oppression further entrench the oppression of animals we perpetrate against one another.

Over the next ten years, if not sooner, I hope the animal rights movement is represented fairly by Black, Indigenous, and people of the global majority who make up most of the world’s population.

I hope that current and future Black activists participating in this movement feel valued and have a safe space to share their efforts. I hope that their insights and perspectives are valued and that they are not tokenized or exploited.

The rodeo protest I attended—where I had been subjected to racial slurs—came to a turbulent end when one of the rodeo-goers began cracking eggs in front of us and throwing them on the ground near our feet. At this point, daylight was long gone, and we began to hear even more intense racist, sexist, and derogatory slurs as the crowd opposing our protest grew larger. The rodeo protest organizer’s organizer ended up calling the police, which scared off many of our detractors.

Shortly after we left, a fellow white activist attending the protest called me, apologized for the racism I experienced, and told me he was truly mortified about how I was treated. It was comforting to know that he cared enough about my experience and wanted me to know that he appreciated my restraint and dedication to the protest.

I would like those working to end the exploitation of animals to understand that as long as race is used as a tool to oppress, it will continue to limit our movement’s growth and our ability to help achieve liberation for all beings.